Fukushima (2011)

8 min read

You can view the interactive 3D model of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant online. In the Free downloads section, you will find the code for inserting the model into your own educational projects.

All commercial nuclear power plants in Japan are located on the coast, as they rely on seawater for reactor and condenser cooling. The Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant is situated on Honshu Island, approximately 90 kilometres south of Sendai. The facility consists of six boiling water reactors (BWRs), commissioned between 1971 and 1979. Due to its coastal location, the plant was known to be vulnerable to tsunami hazards, and a system of protective seawalls and dykes was constructed to withstand waves up to around 7 metres in height.

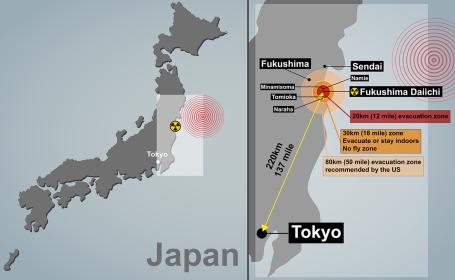

Earthquake epicentre, location of the Fukushima nuclear power plant, the nearest towns and the three evacuation zones are depicted on a map of Japan.

On 11 March 2011, a massive undersea earthquake and subsequent tsunami struck Japan, resulting in nearly 30,000 dead and missing persons. The tsunami significantly exceeded the design assumptions of the plant’s protective barriers.

At 14:46 local time, the so-called Great East Japan Earthquake (also known as the Tōhoku Earthquake), with a magnitude of 9.0 on the moment magnitude scale, occurred approximately 130 kilometres off the Pacific coast. Automatic safety systems inserted control rods into the reactor cores, shutting down the operating units. At Fukushima Daiichi, this affected Units 1, 2 and 3; the remaining reactors (Units 4, 5 and 6) were already in a cold shutdown state for scheduled maintenance. The earthquake itself did not cause significant structural damage to the plant.

Spatial model of the buildings and equipment of the Japanese Fukushima nuclear power plant that was damaged by a large tsunami wave. The system of protective dykes was insufficient and the second largest nuclear accident in the world resulted.

Video animation explaining the operating principle of the BWR light-water, boiling reactor installed at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant (also available in the Free Downloads section).

With the loss of off-site electrical power from the grid, emergency diesel generators automatically started to provide electricity for critical systems, including instrumentation and reactor residual heat removal systems, since a shutdown reactor continues to generate significant decay heat.

Approximately one hour later, however, a tsunami wave at least 14 metres high reached the site. Seawater overtopped the protective barriers, inundating the turbine buildings, flooding equipment rooms, damaging seawater cooling systems, destroying diesel fuel tanks, and submerging backup batteries. As a result, the plant suffered a station blackout, losing almost all on-site power sources.

Model cross section of the boiling water reactor used in the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant blocks.

Without adequate cooling, the reactor cores — still producing around 30 MW of decay heat each — began to overheat. For a short period, some emergency core cooling systems continued to operate on direct current (DC) power supplied by the remaining batteries, but these too were soon depleted. It took approximately eight hours to bring in external power supplies to partially restore cooling capability. However, the damage to the cooling systems and seawater intake structures meant that heat removal remained severely impaired. As a consequence, coolant water began to boil, producing steam and exposing the fuel assemblies, which subsequently began to melt.

Model of the Fukushima nuclear power plant that suffered a great disaster in March 2011. A tsunami wave flooded the machine room, damaged the tanks for diesel generators, leaving the power plant without electricity.

At this stage, the plant operators concluded that only rapid flooding of the reactor cores with seawater could prevent further fuel damage. In order to achieve this, the internal pressure of the reactor vessels had to be reduced, which required the controlled venting of steam into the atmosphere. This procedure inevitably resulted in the release of radioactive material.

More critically, a chemical reaction between the zirconium alloy (zircaloy) fuel cladding and high-temperature steam produced hydrogen gas, which subsequently detonated, causing hydrogen explosions that blew off the roofs of several reactor buildings. Despite this structural damage, the primary containment structures of the reactor pressure vessels remained intact.

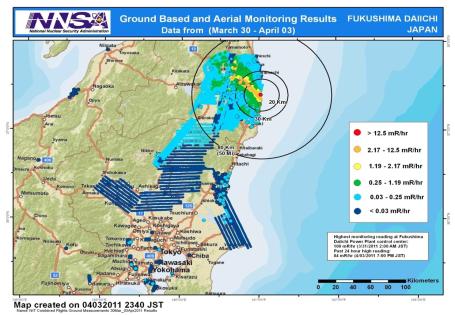

Map of contaminated areas around the plant (22 March — 3 April 2011). Combined results of 211 flight hours of aerial monitoring operations and ground measurements made by DOE, DoD and Japanese monitoring teams.

Unit 4, which was offline for refuelling at the time, was also damaged. The water level in the spent fuel storage pool dropped, leading to increased fuel temperatures and contributing to another hydrogen–air explosion within the reactor building.

Efforts to stabilise the plant continued for the remainder of 2011. During this period, radioactive material was released on several occasions into both the atmosphere and the coastal waters surrounding the site. The total radioactive release from the Fukushima Daiichi plant is estimated to have been approximately 770 × 1015 Bq, composed mainly of iodine-131 and caesium-137.

The evacuation zone around the power plant was progressively expanded to a 20-kilometre radius. No local residents were exposed to radiation doses considered hazardous to human health, and no radiation-induced injuries or illnesses were recorded among the population. A small number of on-site personnel received higher doses during emergency operations — two workers were exposed to approximately 500 mSv, the international occupational dose limit for emergency response personnel. Although no cases of acute radiation syndrome (ARS) were reported, two workers who waded through highly radioactive water suffered beta radiation burns to their lower limbs. Both recovered without long-term health effects.

A number of other personnel were injured or killed as a result of the tsunami impact and falling debris, rather than from radiation exposure.

Video: Model of a boiling water reactor operated in the damaged blocks of the Fukushima nuclear power plant.

Video animation representing the course of the accident at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant (also available in the Free Downloads section).

The Fukushima Daiichi accident was classified as Level 7 on the International Nuclear and Radiological Event Scale (INES) — the highest category — even though its overall consequences were significantly less severe than those of the Chernobyl disaster, which was also rated Level 7. The official investigation into the accident remains ongoing, and it is therefore premature to definitively conclude whether any particular decisions or operational actions worsened the situation.

What is clear, however, is that the Fukushima accident represents the first major nuclear disaster in history primarily triggered by natural forces. It also demonstrated that both human operators and engineering systems worked under unprecedented conditions to mitigate the effects of the event as much as possible.

The incident prompted a renewed wave of public scepticism towards nuclear power worldwide. As a consequence, many nations undertook comprehensive safety reviews of their nuclear installations to verify their resilience against extreme natural phenomena such as earthquakes and tsunamis. Some countries, most notably Germany, temporarily shut down parts of their nuclear fleet or revised their national energy policies in response to the lessons learned from Fukushima.