Nuclear Power Summary

25 min read

The era of understanding and subsequently harnessing nuclear energy began in the late 19th century with the discovery of radioactivity and the study of ionising radiation. Numerous experiments with radioactive materials soon led to a deeper understanding of the structure of matter and the composition of atoms.

Radioactivity

Elements from period one and two of the periodic table, namely, hydrogen, helium, lithium, beryllium, boron, carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, fluorine and neon.

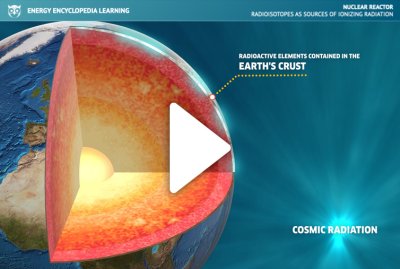

Today, we know that radioactivity is a natural component of our environment, present virtually everywhere around us. Its discovery was a pivotal first step — and a fundamental prerequisite — on the path towards the release and utilisation of nuclear energy.

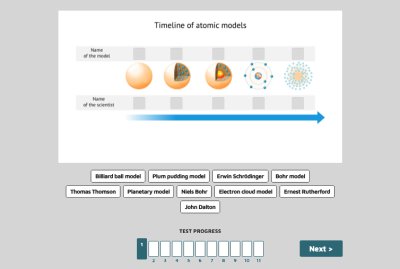

This scientific journey features many remarkable figures. As early as ancient Greece, several centuries BC, Democritus proposed the fundamental idea of matter’s composition, postulating the existence of atoms — small, indivisible, and indestructible particles that constitute the entire universe.

Rutherford experiment with gold foil indicated that the atom is mostly empty space but contains a small, dense, positively charged nucleus.

Centuries later, at the end of the 19th century, Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen opened the door to understanding the internal structure of atoms when he studied mysterious cathode ray emissions capable of penetrating solid materials. Shortly thereafter, Henri Becquerel, while experimenting with phosphorescence, discovered that certain minerals — such as uranium salts — could emit invisible radiation without any external energy source. Building on this work, Marie Skłodowska Curie introduced the term “radioactivity” to describe this phenomenon.

Another crucial piece of the atomic puzzle came with J. J. Thomson’s discovery of the electron, a negatively charged subatomic particle. Since atoms were assumed to be electrically neutral, Thomson imagined electrons as raisins embedded in a positively charged “pudding”, a concept later known as the plum pudding model of the atom.

Schematic drawing of the bombardment of a gold atom by alpha particles that are reflected from the nucleus of the atom.

The nature of radiation was further explored by Ernest Rutherford, who classified it into three types: alpha (α), beta (β), and gamma (γ) radiation. Most importantly, through his famous gold foil experiment, in which alpha particles bombarded a thin sheet of gold, Rutherford demonstrated that nearly all of an atom’s mass is concentrated in a very small nucleus, around which electrons orbit. The nucleus is roughly ten thousand times smaller than the atom itself.

The energy levels of these electron orbits were later explained using quantum physics by Niels Bohr, who thereby defined the fundamental atomic model still used today. To complete the picture, scientists needed to understand the composition of the nucleus itself. The proton, a positively charged subatomic particle, was discovered by Rutherford in the early 20th century, and the final missing piece, the neutron, was identified by James Chadwick in 1932.

You can download the animation of the uranium nucleus model from the Free Downloads section.

The number of protons in an atomic nucleus uniquely identifies a chemical element. Atoms with the same number of protons but different numbers of neutrons in the nucleus are known as isotopes of that element. All isotopes of a given element share the same chemical properties, but due to differences in nuclear mass, their physical properties vary.

Some isotopes are unstable, and their nuclei achieve a more stable proton-to-neutron ratio by emitting particles — a process known as radioactive decay or nuclear transmutation.

Ionising Radiation

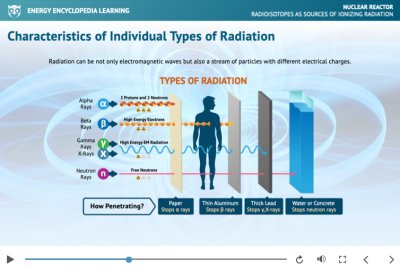

The illustration shows which materials can stop the penetration of different types of radiation.

Ionising radiation is an inherent and inseparable part of the natural environment. Its primary sources are naturally occurring radioactive elements. The term does not refer exclusively to electromagnetic waves; it also encompasses streams of particles. Ionising radiation has the ability to remove electrons from atoms, thereby producing ionisation.

Alpha radiation (α) consists of a stream of positively charged helium nuclei. It is deflected by a magnetic field and has a very limited penetration depth; even a sheet of paper is sufficient to stop alpha particles.

Beta radiation (β) is essentially a stream of negatively charged electrons or positively charged positrons. Because beta particles are much lighter than alpha particles, they have a greater penetrating ability. A shielding layer of just a few millimetres of aluminium is usually adequate for protection.

Gamma radiation (γ) is also a stream of particles, but in this case it consists of high-energy photons with very high penetration capability. As a form of indirectly ionising radiation, gamma rays are unaffected by magnetic fields and require thick layers of lead to provide effective shielding.

The graph shows the relationship between the intensity of transmitted radiation and the thickness of shielding for different types of absorbing materials.

Other types of indirectly ionising radiation include X-rays and streams of neutrons or protons. X-radiation is short-wavelength electromagnetic radiation (with a wavelength between 10 nm and 100 pm) that is not generated by nuclear processes, but rather during interactions of high-energy electrons, for example in a cathode ray tube. From the perspective of its origin, X-rays are classified as bremsstrahlung (braking radiation) or characteristic radiation, and they can be shielded using thick layers of concrete or lead.

Neutron radiation is a type of ionising radiation consisting of a stream of free neutrons. It is produced primarily during the fission of heavy nuclei in nuclear reactors or through interactions between alpha-emitting sources and light elements. Like gamma rays, neutron radiation is a form of indirect ionising radiation, as the ionisation is caused by secondary particles generated during neutron interactions with matter.

High-energy protons are a significant component of cosmic radiation that reaches Earth from outer space. Upon colliding with the upper atmosphere, these protons generate a cascade of secondary radiation.

Natural Sources

Schematics of the Van Allen belts protecting the Earth against corpuscular radiation.

Sources of ionising radiation are present all around us. Radioactive isotopes of various elements occur naturally in the soil, air, water, food, and even within the human body. Collectively, they are referred to as natural sources, and the dose of radiation we receive from them is known as the natural background radiation.

A major part of the total annual dose of ionising radiation originates from natural sources, while the remainder comes from man-made sources, particularly those used in medicine. Exposure from natural sources is far from uniform across the Earth — in some regions, dose rate levels may exceed the global average by one or two orders of magnitude.

One of the fundamental natural sources is cosmic radiation, which reaches the Earth from the Sun or from interstellar space. It consists of a stream of high-energy particles, primarily protons. Only a small fraction of this radiation reaches the Earth’s surface. Most primary particles collide with atoms in the upper atmosphere, generating showers of secondary radiation.

Animation showing the seepage of inert radon gas into residential buildings.

The air and soil are among the most significant natural sources of radiation on Earth. The presence of radioactive noble gases such as radon and thoron, produced by the decay of uranium and thorium, is a major contributor to elevated airborne dose rates.

The occurrence of these gases varies considerably and depends primarily on the geological composition of the underlying strata. The accumulation of hazardous radon inside buildings can be mitigated through adequate ventilation and the installation of radon barriers between the ground and the structure.

Rocks and soil also contribute to the total radiation dose. Volcanic rocks such as basalt and granite typically contain higher concentrations of radioactive elements, including uranium and thorium. Consequently, construction materials produced from such rocks can also serve as sources of ionising radiation.

Radioactive elements migrate from rocks into the soil, are absorbed by plants, and subsequently enter the entire food chain. As a result, all foodstuffs and drinks we consume exhibit a small degree of natural radioactivity. The specific activity varies — depending on the composition of the soil where plants were grown and on the ability of certain plants or animals to accumulate radioactive elements.

Perhaps unexpectedly, the human body itself is also a source of ionising radiation. It contains radioactive isotopes of elements such as carbon, potassium, and various trace elements, leading to several thousand radioactive decays occurring every second within the human body.

Man-made Sources

Proportion of natural and man-made radiation sources in the overall dose.

In recent decades, the use of man-made sources of ionising radiation has expanded significantly. These sources are primarily employed in medicine for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes, in industry and energy production, in scientific research, and in many other fields. Exposure from man-made sources is relatively limited, contributing less than 20% to the total annual radiation dose. This relatively small share is mainly the result of radiation protection measures and strict regulatory controls.

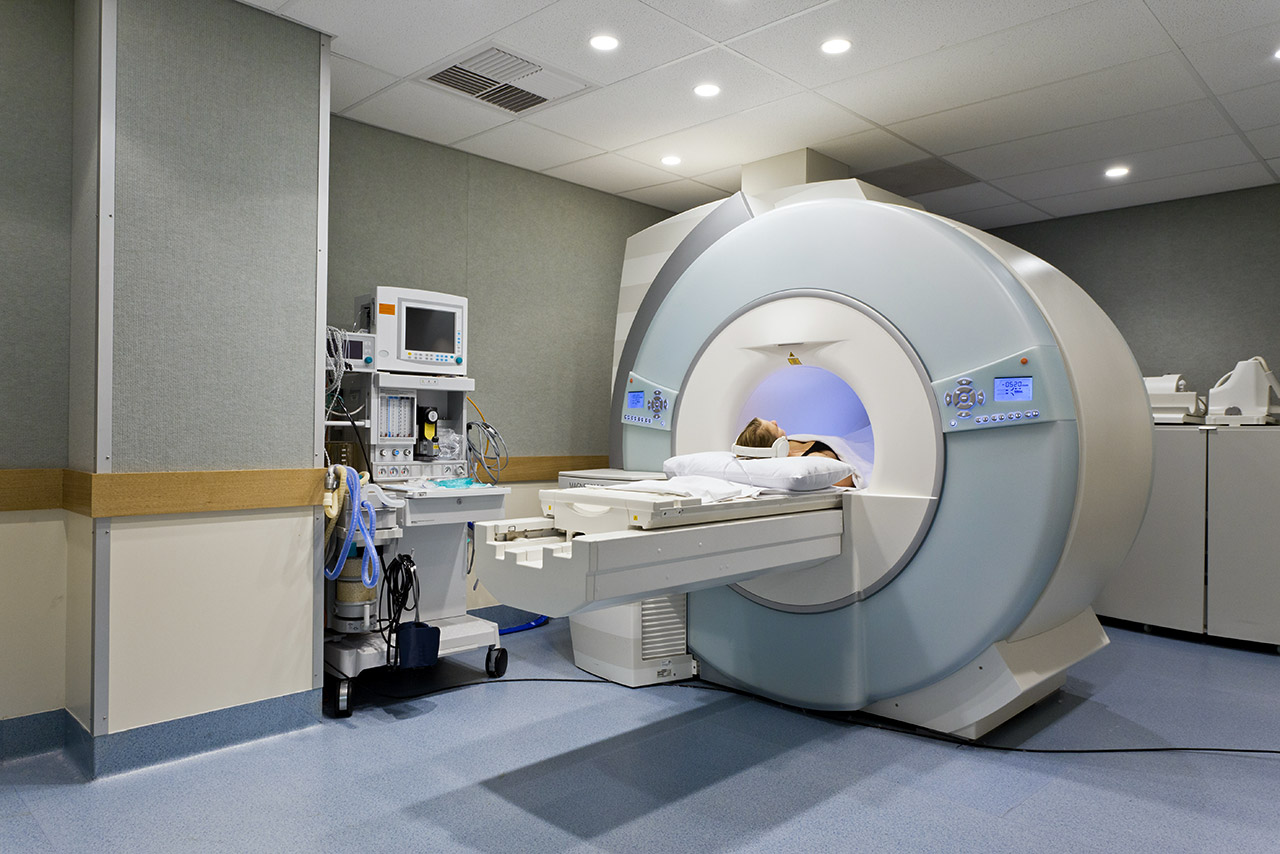

The most prominent area of application for man-made radioactive sources is medicine. Here, radiation is used both for diagnostic purposes — such as radiography, fluoroscopy, and computed tomography (CT) — and for therapeutic treatments, including radiotherapy and brachytherapy.

The administration of liquid open radioactive isotopes into the body, a practice known as nuclear medicine, enables the acquisition of imaging data on the structure and function of specific organs.

Model of a medical X-ray device for mammogram breast examination.

High-intensity gamma sources are employed for sterilising surgical instruments, as well as for the protection of cultural heritage objects against wood-boring insects and fungal damage, and even for extending the shelf life of food.

Certain radioisotopes are successfully used as tracers to detect leakages in complex technological systems or to monitor the distribution and absorption of newly developed pharmaceuticals in the human body. Other isotopes assist in the examination of internal material structures, the assessment of weld quality in critical constructions, or the detection of invisible defects in industrial components.

Perhaps the most feared man-made source of ionising radiation is highly radioactive spent nuclear fuel from nuclear power plants. Although it is an intense source of radiation, it is highly concentrated, well shielded from the environment, and stored in strictly regulated interim storage facilities or final repositories, resulting in a negligible contribution to public radiation exposure.

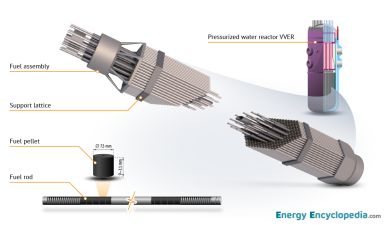

Fuel pellet, fuel rod, and fuel assembly from a VVER pressurized water reactor.

Interestingly, coal-fired power plants contribute approximately three times more to the local population’s radiation dose than nuclear power plants. This is due to the presence of trace amounts of uranium, thorium, radium, lead, and potassium in coal, which become concentrated in fly ash during combustion.

Artificial sources of radiation are also encountered in a wide variety of other contexts — from superphosphate fertilisers to uranium-coloured glass. Even domestic smoke detectors utilise trace amounts of radioisotopes as part of their sensing mechanism.

Half-life

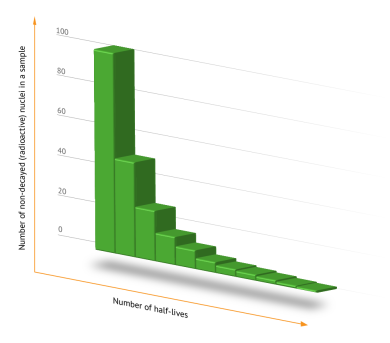

A graph showing the decrease in the amount of radioactive isotope in the sample over several half-lives.

The half-life is the period of time during which approximately half of the atoms of a given radioactive isotope undergo decay, regardless of how many atoms were present initially. This means that half of the original atoms decay during the first half-life, and half of the remaining atoms decay during the second, leaving one quarter of the original quantity. After ten half-lives, about 99.9% of the original radioactive material will have decayed. This fundamental relationship was first described by Ernest Rutherford. The half-lives of different isotopes range from a few nanoseconds to millions of years.

The graph shows the distribution of stable isotopes, naturally occurring radioactive isotopes, and man-made radioactive isotopes.

In medicine, short-lived isotopes — such as iodine-131 (131I) and technetium-99m (99mTc) — are widely used because they decay rapidly within the patient’s body. The principle of half-life is also the basis of radiocarbon dating, which uses the decay of carbon-14 (14C) to determine the age of biological materials. By precisely measuring the total carbon content and the proportion of radioactive carbon isotopes, it is possible to calculate how much time has elapsed since a plant died — for example, when it was used to build a ship. The ratio of radioactive to stable carbon isotopes is fixed during the plant’s life. Therefore, if a sample contains half of the original radioactive carbon, its age is one half-life, or 5,730 years.

To date much older rocks, scientists use the principles of uranium decay, a process in which alpha particles are emitted. These alpha particles capture electrons and become helium atoms. Thus, the age of a rock sample can be determined simply by measuring the amount of helium present.

Decay Series

Uranium series. The four fundamental radioactive decay series (thorium, neptunium, uranium, and actinium).

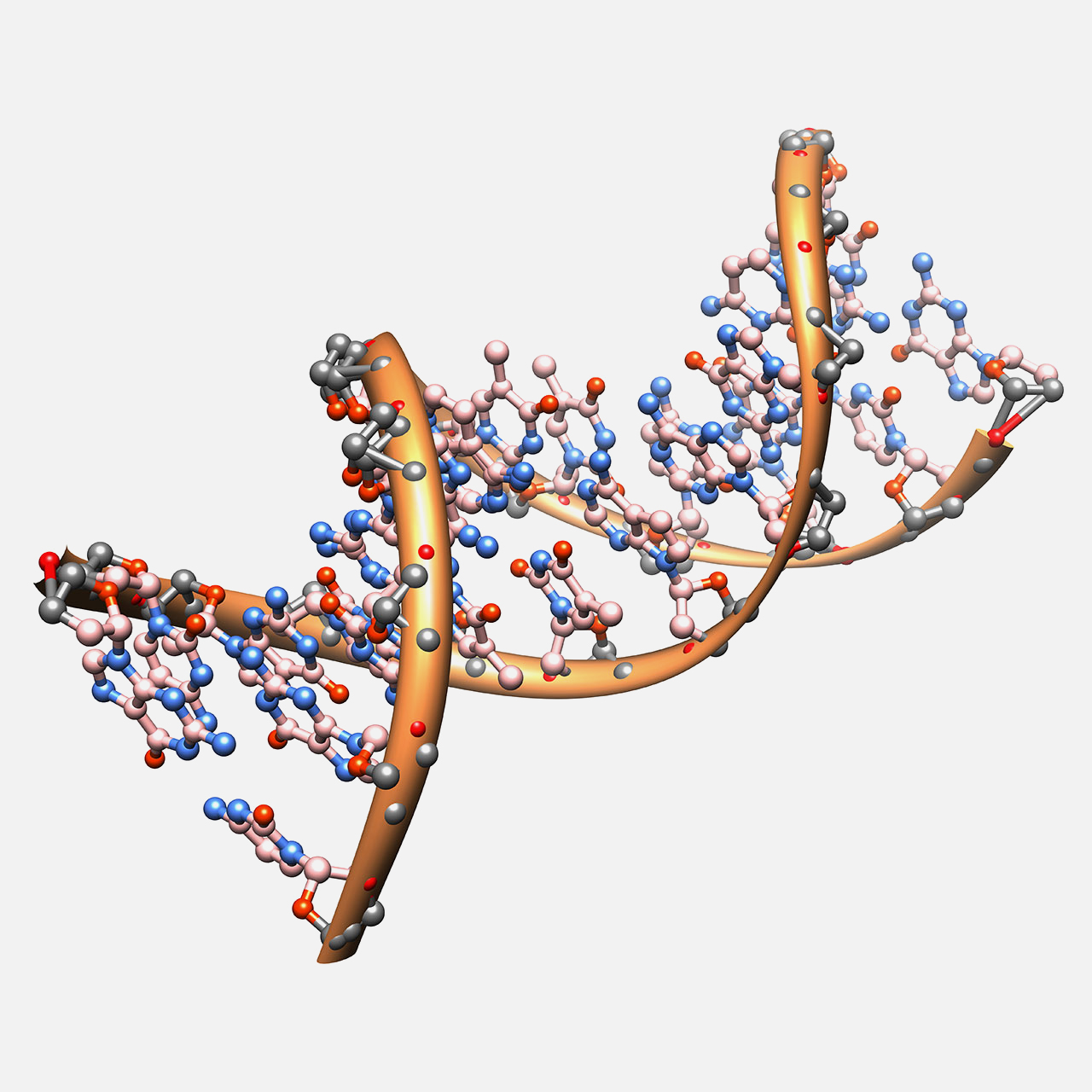

Radioisotopes do not usually decay directly into stable elements. Instead, they transform through a sequence of successive decays that ultimately lead to a stable end product. This sequence is known as a radioactive decay series.

A decay series comprises a range of radionuclides with different half-lives, and it describes their step-by-step transformation. In some cases, a radionuclide in the series can decay via two different pathways, resulting in branching of the series.

There are four fundamental decay series: the thorium, neptunium, uranium, and actinium series. Each is named after the radionuclide with the longest half-life within the chain. During the decay process, either alpha particles are emitted — reducing the mass number by 4 — or beta particles are emitted, which do not change the mass number but increase the proton number by one.

Knowledge of decay series enables scientists to determine the original composition of rocks, even when the parent isotopes have long since decayed.

Quantities and Units

Video presenting one of the types of personal dosimeters used can be found in the Free download section.

The behaviour and effects of radioactive substances and ionising radiation are quantified using a set of fundamental physical quantities and measured in corresponding units.

The simple rate of radioactive transformations occurring in a material is known as its activity. The SI unit of activity is the becquerel (Bq), although the older unit curie (Ci) is still sometimes encountered. An activity of one becquerel (1 Bq) corresponds to one radioactive decay per second within a given sample.

1 curie = 3.7 × 1010 Bq

To evaluate the effect of radiation on a material, the key quantity is the absorbed dose — the amount of energy deposited per unit mass of the substance. It is measured in grays (Gy), where 1 gray (1 Gy) equals 1 joule of energy absorbed by 1 kilogram of material. The older unit of absorbed dose is the rad.

1 rad = 0.01 Gy

Schematic diagram of a pocket dosimeter which indicates the amount of radiation dose received by the wearer.

Because different types of radiation have different biological effects on living tissue, the concept of equivalent dose is used to represent the biological effectiveness of the radiation. It is measured in sieverts (Sv), or in the older unit rem.

The dose rate expresses the amount of radiation dose received over a specific period of time, such as per minute or per year. When assessing radiation exposure in humans, the equivalent dose rate is expressed in Sv/s. Because the sievert is a relatively large unit, microsieverts per hour (µSv/h) or millisieverts per year (mSv/year) are more commonly used.

Various types of detectors are used to detect ionising radiation in both laboratory and operational environments. Despite differences in design, all detectors operate on the same basic principle: radiation passing through the detector produces a measurable physical effect. The most common types include: Scintillation detectors; Trace detectors; Semiconductor detectors.

Schematic diagram of a film dosimeter which, by changing the colour of the film, indicates the amount of the dose received by the wearer.

Other detectors are based on the ionisation chamber principle, where an inert gas or, in some cases, water or alcohol vapour is ionised by the passing radiation. One notable example is the Wilson diffusion cloud chamber, which is unique in enabling the direct visualisation of ionising radiation as it passes through the detector.

To measure the radiation dose received by a person, dosimeters are employed.

In a film dosimeter, particles passing through the device cause gradual darkening of the photographic film — the greater the radiation dose, the more intense the darkening.

A thermoluminescent dosimeter (TLD) works on a different principle: it measures the light emitted when excited electrons — raised to higher energy states by radiation exposure — return to their ground state.

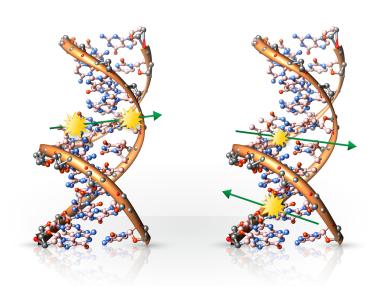

Effects of Ionising Radiation

Ionising radiation has the ability to dislodge electrons from atoms through which it passes. This interaction can lead to molecular damage or structural changes in matter. In the case of living cells, such radiation can severely damage or even destroy the cell. Minor damage can usually be repaired by the cell’s natural mechanisms and therefore poses no significant threat to living organisms. However, extensive damage to DNA may result in various mutations and altered cellular behaviour.

Slightly increased radiation doses can stimulate the body’s repair mechanisms, enhancing its ability to eliminate cancerous cells. Conversely, high doses of radiation can cause severe tissue damage, organ failure, and ultimately death.

Principle of the gamma knife for targeted brain treatment.

In medicine, targeted high doses of radiation are employed to treat malignant tumours, as cancer cells are highly sensitive to radiation. The radiation source may be introduced directly into the tumour via injection (in the case of alpha sources), or external sources may be used, with their beams precisely focused to intersect at the tumour site (gamma sources). The proven therapeutic effects of lower radiation doses have also been utilised for many years in radioactive spa treatments.

If you are interested in the design of the pressure vessel of the most widely used PWR reactor, you can view it online in the 3D Models section or download the embed code from Free Downloads.

Irradiation has specific applications in the modification of industrial materials. Radiation-based technologies enable the production of materials with entirely new properties without the use of undesirable chemical additives. Radiation can be used to cure coatings, alter the properties of textiles, or change the colour of glass. It is also used in the production of laminates, polymer foams, and to induce the “memory effect” in polyethylene during the manufacture of shrinkable materials.

On the other hand, radiation-induced embrittlement can alter the structure of metals. For this reason, the pressure vessel of a nuclear reactor must be made from specially engineered alloys capable of withstanding neutron flux for up to eighty years.

Activity and Doses

Our bodies are exposed to a certain level of radiation dose during almost every activity. For example, consuming a single banana exposes the body to a dose of approximately 0.1 µSv. By contrast, living for one year in the Brazilian city of Guarapari would result in exposure to a dose of around 175 mSv.

There is also a significant variation in the activity of various products and materials. For instance, 1 kg of coffee has a radioactivity of about 1,000 Bq, while americium contained in a household smoke detector reaches approximately 30,000 Bq. By comparison, 1 kg of uranium ore exhibits an activity of roughly 25 million Bq.